|

|

|

|

|

Unit 4:

|

|

Guide for Teachers and Students

|

|

|

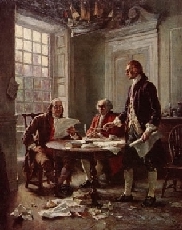

The problems of slavery and race have presented the major challenge to the principles and practice of American liberalism. Can American liberalism withstand this challenge? To answer that question we will examine the writings of two thinkers who had a tremendous influence on the American political consciousness, John Locke and Thomas Jefferson, and the writings of four of the most thoughtful commentators on race in America, Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington, W. E. B. DuBois, and Martin Luther King, Jr. We will then see how the concerns of these writers are reflected in four films, Amistad, Glory, Separate But Equal, and Lone Star. Together, these writings and films will help us to better understand the issue of race in America and the character of American liberalism. John Locke's Second Treatise on Government is one of the first and the most important statements of liberal political theory. In his chapter "On Paternal Authority," Locke attacks the legitimacy of monarchic government by explaining the distinction between political and paternal authority. First he points out that the idea of paternal authority is itself inconsistent with the natural fact that individuals have two parents—a mother as well as a father. If one owes allegiance to his or her father as a source of being, he or she owes equal allegiance to a mother. Nature, he concludes, does not support one-man rule. Even within the family, Locke argues, that a parent does not have unlimited authority over a child. The relationship is as much one of duty as of power. The parent exercises authority over the child for the benefit of the child. The parent guides and protects the child until the child is capable of acting independently. Once the child no longer requires such guidance, the legitimate basis of parental authority disappears. For Locke, there is no natural basis for one mature individual to exercise power over another. The Declaration of Independence builds upon these Lockean principles. Jefferson describes Locke's principle of equality as a self-evident truth. Jefferson does not mean that individuals are equal in all respects, but following Locke, he says that they are equal in their political rights. No one has a right to rule over another unless the individual freely consents to such rule. Jefferson goes on to explain that governments are necessary to protect natural rights. We give up some of our rights in order to gain greater security against the intrusion of our rights by others. Political authority is necessary and legitimate as long as it is grounded in consent of the governed and used for the protection of rights. There would appear to be little room for political distinctions based on race in the Lockean-Jeffersonian framework. But as we all know the author of the Declaration owned slaves, and the government created after the American Revolution tolerated slavery. Were the words of the Declaration meaningless? Or, did they raise up a standard for political authority that would ultimately serve as a major weapon in the attack on the institution of slavery? Frederick Douglass's autobiography clearly illustrates the conflict between the principles of human equality and the practice of slavery. One of the most destructive aspects of slavery was the destruction of the family. Douglass tells how he was separated from his mother almost from birth, and never knew the identity of his father. The love and nurture described by Locke and enjoyed by many white Americans was denied to Douglass. This destruction of the family was the first step in the attempted transformation of an individual into a piece of property. Although education might have made the "master's property" more valuable, Douglass explains that masters understood the threat education posed for the institution of slavery. Educated slaves would be unwilling to accept their status as slaves. Moreover, if slaves could be educated, a major premise underlying slavery, the inhumanity of slaves, would be demolished. Rather than educate slaves, masters had to be willing to practice the most heinous forms of cruelty in order to restrain any human impulse toward freedom that a slave might possess. The need for such cruelty, Douglass shows, inevitably had an effect on white masters. They could not seek to break the slave without degrading their own humanity. Douglass's own story demonstrates that even in the face of the most draconian measures practiced by the slaveholders, the humanity of the slave could not be extinguished. Douglass came to understand his own worth and his own potential. He taught himself to read and write, and when faced with the brutality of a slave-breaker, he refused to be broken. Through the story of his victory over slavery, Douglass provides irrefutable evidence of the humanity of slaves. Douglass knew what he had done for himself against almost impossible odds, but his "Oration in Memory of Abraham Lincoln," displays his willingness to recognize the help of others. Douglass believed that his ability to show such gratitude was an essential step in the achievement of racial equality. Douglass's praise of Lincoln may sound strange to ears accustomed to unqualified flattery. Douglass begins by pointing to the different interests and outlooks separating Lincoln from African Americans. He says that Lincoln was first and foremost the white man's President. But far from detracting from his praise of Lincoln, his honest statement of differences serves to highlight the extraordinary character of Lincoln's achievement. By linking the interests of his own race to the rights of all people, including slaves, Lincoln showed that at least in some respects the differences between races were less important than their common humanity. In recognizing Lincoln's accomplishment Douglass illustrated that wise political leaders of both races might remain true to their own distinct interests and identities, yet at the same time seek a common ground. What would be the basis of that common ground following the Civil War? Could the inequities that existed even in the absence of slavery be overcome? Booker T Washington, W. E. B. DuBois, and Martin Luther King offered different approaches for addressing these questions. Washington believed that equality and independence could be achieved through a gradual process of self-improvement. Freedom could not exist unless individuals were capable of providing for their own necessities of life. According to Washington, society had to be built from the bottom up. If former slaves could not learn to care for themselves, they would forever be dependent upon and under the control of the white race. Washington hoped that in the process of learning to take care of themselves, African Americans would develop the skills and talents that would make them more valuable to the community as a whole. These skills and talents would allow them to be full participants in the free market economy, and that in turn would break down the barriers between the races. W. E. B. DuBois complained that Washington's approach failed to recognize the importance of higher education to the growth of African American society. He claimed that building only from the bottom up was not only too slow, but was also ultimately impossible. DuBois argued that any group ultimately depends upon its exceptional individuals to lead it to success. These individuals are not only the educators but also the models who offer a vision to a people of their highest possibilities. Unlike Washington, DuBois suggests an aristocratic means to the end of racial equality. By the 1960s it was obvious to Martin Luther King that neither Washington's nor DuBois's vision could become a reality if the ongoing legal barriers to racial equality were not eliminated. In his "Letter From a Birmingham Jail" King explained that whatever merits Washington may have found in gradualism, after 100 years the time for gradualism had passed. King was convinced that change would only come through direct and immediate action. Segregation could no longer be tolerated. King's vision, nonetheless, was one of restraint. He eschewed violence in favor of peaceful civil obedience. He understood that it was those who had suffered injustice, who were doomed to suffer more by this approach. But he believed that no other way was consistent with his principles of justice. His ultimate goal was not just victory for African Americans, but victory over prejudice for all Americans. His "I Have a Dream Speech" calls for the fulfillment, not the rejection of the principles expressed by Locke and Jefferson. He called on Americans to rise above their prejudices and recognize their common belief in the dignity of all human beings. Each of the films we have selected amplifies the themes found in these writings. Amistad tells the story of a rebellion on a slave ship, Glory explores the different views of the African Americans who made up the first black regiment to fight in the Civil War. Separate But Equal is a dramatic account of the Supreme Court case that led to the abolition of legal segregation. Finally, Lone Star looks at race relations forty years after Brown, and the changing racial makeup of the United States. Amistad illustrates the evils of the slave trade in the same way that Douglass's Narrative portrayed the life of a slave in the United States. It shows the power of the drive for freedom and the ability of the slaves to organize a rebellion and sail an ocean-going ship, the likes of which they had never seen. It then proceeds to examine the legal status of slavery in our liberal democracy. The young attorney explains the legal contradiction inherent in the idea of slaves as property. If slaves are property they cannot be held accountable for their actions, and hence should not be executed for crimes. Moreover, if these individuals were not born into slavery in the United States, they cannot be considered property under the laws of the United States. Instead they must be considered as individuals, with the rights of individuals. Former President John Quincy Adams, suggested a different legal strategy. He thought it crucial to explain to the Court the story of the rebellion's leader Cinque, the story of who he was and where he came from. In so doing Adams hoped to impress upon the Court that Cinque was a person, not a piece of property. Adams also expanded the legal argument. Because the Africans on the Amistad were outside the jurisdiction of the positive laws of the Southern states, Adams was able to move the argument from the practices of particular states to the natural rights foundations underlying the national government. He contended that the principles of the Declaration had never supported slavery. Slavery was an exception, a compromise that left the nation unfinished. Just as Cinque says that he will call on his ancestors for help, John Quincy Adams turns to the principles that guided his father and the generation of the Revolution into action. Cinque and his shipmates were freed and returned to their homeland, but the end of the story was far from happy. Cinque returns to a civil war. His family is missing, probably captured and sold into slavery by other Africans. In America slavery remained. It would take our own civil war to abolish it. Glory tells the story of an often neglected chapter of the Civil War. Robert Gould Shaw is the young officer charged with training the first regiment of African American soldiers. At the beginning of the film Shaw is committed to the abolition of slavery, the war, and the Union, but he is naïve in his understanding of those commitments. The war that he thought was necessary and noble he soon finds is also horrible. But his recognition of this fact does not diminish his belief in the war's necessity and in some way increases his belief in its nobility. His dedication to abolition is raised to a new level by his experience with his African American soldiers, but in addition he learns that abolition is only a first step toward freedom. Finally, he learns of the difficulty of creating and maintaining a union. He discovers that many on the side of the Union are scoundrels, and that among his own troops there is much disagreement about the meaning of the American Union. Nonetheless, he is heartened in the end by the story of his regiment, a story he wants to be remembered. In telling it, however, there is the danger that it may appear to be a patronizing story of what a white officer did for his black troops. The movie overcomes this problem by its careful development of the different stories of the individual soldiers. In some respects these stories reflect many of the concerns we have seen in the writings of Douglass, Washington, and DuBois. Rawlins who begins the film as a gravedigger, and Thomas who begins as an intellectual in some respects embody the debate between Washington and DuBois on the meaning of freedom. At the beginning of the film Trip is like the young Frederick Douglass who refused to be broken, and by the end he is like the Douglass who frankly admits his differences with Lincoln, but also recognizes their common vision, as they die together in battle. The film Separate But Equal dramatizes the differences among civil rights leaders as to the best strategy for ending segregation as well as the debates surrounding the Supreme Court's decision in Brown v. Board of Education. The first question for the civil rights leaders was whether to focus on the unequal conditions in segregated schools or to attack directly the legitimacy of segregation. In the end the plaintiffs are left with no choice but to discredit segregation in all forms. The problem with which they are then faced, however, is that both legal precedent and longstanding practice support segregation. To overcome these presumptions in favor of segregation they must prove that segregation in and of itself violates the equal protection clause of the fourteenth amendment. The movie explores the different possible approaches to establishing such proof. The attorneys first turn to social science in order to demonstrate the effects of segregation on the hearts and minds of children. They argue that the results of the now famous "doll test" were prima-facie evidence of the inequality inherent in segregation. But this alone was not sufficient to sway the justices. The question that recurs in the film is whether there is any legal basis for the Court to end segregation. In the end some of the justices remain unpersuaded by the legal arguments, but they vote to strike down segregation because they believe it is the morally right thing to do. They seem to think that in this case there is an unbridgeable gap between the legal and the moral. But Justice Frankfurter's clerk does not believe that this gap is so large. He contends that the 14th Amendment has long been used to protect the rights of individuals against unequal treatment by the government. All the plaintiffs were asking in this case was to apply those protections to the primary group for which the Amendment was written. In his final argument before the Court the attorney for the plaintiffs, Thurgood Marshall develops this line of reasoning even farther. He asks the Court what is the ultimate rationale for the practice of state sponsored segregation. He claims that there is only one possible rationale, the belief in the inferiority of African Americans. It is that assumption that flies in the face of the 14th Amendment and the principle of human equality that lies at the foundation of liberal government. The opinion of the Court is not quite so clear in its rationale. The Chief Justice draws on many strains of the argument against segregation to explain the Court's decision. In some way that is fitting given the complex judicial politics that went into creating a unanimous Court. But at least in this case, the simplest argument may be the most true. Segregation rested on a principle no one was willing to defend. In the final analysis Americans believed in the principles of the Declaration of Independence. As a movie Lone Star defies classification. It is part mystery, part western, part social commentary, and part family drama. The writer-director John Sayles breaks down the lines between these genres in a story that questions many of the lines that are typically drawn by conventional society. The most prominent theme of the movie is the importance of the past and our understanding of it. Sam, the main character, thinks his father committed a murder, and he spends most of the movie trying to uncover the past. In the end he finds that the past was not what he thought it was, and we are left wondering whether he is better off knowing the truth. The movie examines the life of three families, one white, one African American, and one Hispanic. Initially it seems to point to the ongoing differences between these cultures. They live in the same town, but seem to exist on parallel planes, only meeting at the fringes of their lives. But as the movie progresses we see that although their individual problems, particularly their problems with their families, take different forms, the generational conflicts in each case are remarkably similar. Moreover, we learn by the end of the movie that their lives were much more intertwined than we realized. The older generation, Buddy Deeds, the white sheriff, Hollis the white deputy and later mayor, Otis the black bar owner, and Mercedes, the Hispanic businesswoman had long ago transcended racial barriers. The younger generation of Sam and Pilar had been kept apart not because of their differences, but because of what they had in common. Not only could this movie be characterized as a post civil rights movie, it may also be described as a post rights movie. It points to questions that may not be answered by the principles of the Declaration or John Locke. Who are we other than rights bearing individuals? Can we ever simply make ourselves? Can we ever forget the past? Should we try? How much of ourselves is determined by the stories that we hear and tell about our past? Just as African American thinkers such as Douglass, Washington,

DuBois, and King were forced to think about the conditions of freedom,

Sayles asks us to explore the character and extent of our freedom

as individuals. There is no question that his characters have a

right to choose. The future is in some respects like the blank drive-in

screen at the end of Sayles's film. It is our job to fill it. But

those who look at the screen, those who must choose are not blank

slates. They are formed by what has come before and how they understand

it. |